HIAA concentrators, Simone Straus and Camille Blanco, will present at the 2025 SUNY New Paltz Undergraduate Art History Symposium. These students' presentations arise from HIAA courses: Camile wrote the paper she will present for visiting lecturer Annie Maloney’s class last semester, and Simone’s presentation is her Capstone project, which she wrote with affiliated Prof. Stephen Houston. HIAA PhD candidate, Pamudu Tennakoon, will also participate in a panel.

The event will take place online from April 3-7, 2025. Read below the abstracts of our concentrators' presentations:

Thursday, April 3

2:15 PM Camille Blanco

“The Chisel’s in the Details: Restoring Ancient Sculpture in the Ludovisi Collection”

Maarten van Heemskerck (1498–1574), Lower Statue Court of the Casa Galli, ca. 1532-1536, engraving (pen in iron gall ink). 79 D 2, fol. 72 recto, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. (Image: Dietmar Katz.)

The rediscovery of Greco-Roman antiquity during the Renaissance sent the city of Rome into a frenzy. As popes began sponsoring excavations of Roman sculpture, their intent was to strengthen the papal seat of power through Rome’s legacy as the glory of antiquity. Such an interest in an important albeit fragmentary ancient past suggested, to the men who engaged with it, elevated intellects and refined sensibilities. Close to one hundred years later, the allure of antiquity for artists, antiquarians, and collectors lay in its capacity to be presented as whole, rather than fragmented, works of art. Thus, the profession of the sculptor-as-restorer grew in popularity as artists excelled in transforming part to whole with works that boasted a dynamic weaving of ancient and modern forms that completed what time failed to protect. Once the stronghold of the Roman Empire for thousands of years, Rome again rose to prominence as the epicenter of the Baroque. My paper investigates the specific values of antiquity that were transposed through Baroque restorations of Greco-Roman statuary depicting divinities in Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi’s famed antiquities collection. Through a careful review of how Baroque artists interacted with ancient artifacts regarding taste and reception, I consider two well-known seventeenth-century restorations, Gianlorenzo Bernini’s Ares Ludovisi and Alessandro Algardi’s Hermes Ludovisi, which are still on view today at the Museo Nazionale Romano. This project promotes a reconsideration of the unique perspectives and limitless imaginations that Bernini and Algardi brought to their restorations, crafting a distinctly Baroque ‘New Rome,’ neither ancient nor modern, but something in between. I argue that these restorations were Cardinal Ludovisi’s way of appropriating and manipulating antiquity to establish himself and his legacy through his desire to revive ancient Rome.

Image: Maarten van Heemskerck (1498–1574), Lower Statue Court of the Casa Galli, ca. 1532-1536, engraving (pen in iron gall ink). 79 D 2, fol. 72 recto, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. (Image: Dietmar Katz.)

Monday, April 7

7:00 PM Simone Straus

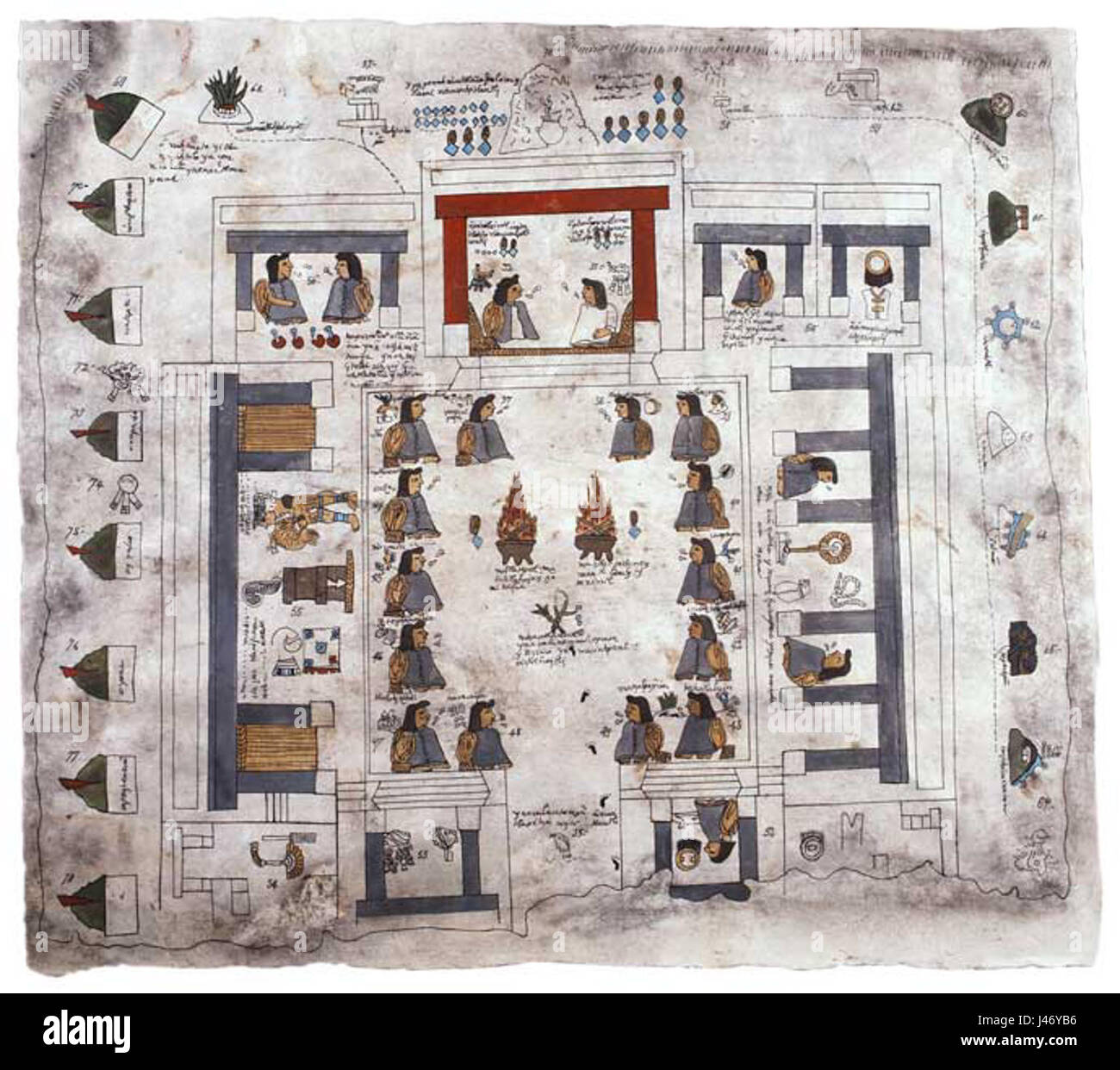

“The Fabric of Space and Place: El Lienzo de Tlaxcala”

Art has the power to shape history—not just in what it records, but in how it tells the story. The Lienzo de Tlaxcala, a sixteenth-century pictorial manuscript, is more than a chronicle of conquest; it is a visual argument that intentionally uses labels, symbolism, and spatial organization to craft a version of history in which Tlaxcala is not merely a supporting player in Spain’s victory over the Aztecs, but a central force in bringing down the Mexica Aztec. Commissioned in 1552, the lienzo is composed of over eighty meticulously arranged scenes, unfolding in a structured grid that guides the viewer’s eye in a left-to-right, top-to-bottom rhythm reminiscent of European print culture. Yet, within this imported framework, indigenous artistic strategies are also present. Glyphs and place signs anchor the narrative in space, ensuring that geography is not just a backdrop but an active force in the conquest’s unfolding. Tlaxcala, positioned at the physical and thematic center of the composition, emerges as the star of the campaign, with its strategic alliances and military contributions given visual prominence through hierarchical scaling, repetition, and emphasis. The lienzo does not simply document movement—it constructs it. Figures step forward with bent knees, horses rear mid-gallop, and winding paths connect key locations, transforming a static cloth into a dynamic war story. Bodies of water serve as both narrative dividers and structuring devices, guiding the eye and reinforcing the spatial organization of the lienzo. Even the placement of Spanish churches and imperial insignia, often read as symbols of colonial domination, subtly work within the lienzo’s narrative to reinforce Tlaxcala’s agency in shaping the new world order. More than a map, more than a manuscript, the Lienzo de Tlaxcala is an assertion of power. Through its deliberate use of labels, symbols, and composition, it cements Tlaxcala’s role as a main player in the conquest of the Aztecs—not just in the past, but in the historical memory that followed.

Learn more about the symposium here.